Picture a city street during twilight, quiet except for the growing noise of a unified deep groan. Abruptly, a group of disheveled, injured beings emerge, their feet dragging across the sidewalk, their empty eyes fixed on people running away in fear.

A classic movie monster, the zombie became widely popularin the 21st century, a period marked by worldwide concern – the financial crisis, the threat of environmental changes, the ongoing effects of the 9/11 attacks, and the outbreak of the COVID-19 virus.

The zombie outbreak turned into a means for individuals toexamine the horrifying idea of civilization's breakdown, somewhat distant from actual dangers like nuclear conflict or worldwide economic collapse.

As a public health epidemiologistAnd being an amateur zombie historian, I couldn't help but observe the remarkable similarities between what epidemiologists do to prevent infectious disease outbreaks and what heroes in horror movies do to stop zombies. The main questions raised in any zombie story—how did this begin, how many people are infected, and how to contain it—are exactly the same questions that epidemiologists address during a real infectious disease outbreak or pandemic.

In 2011, indeed, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released azombie apocalypse preparedness guidethat outlined how preparing for a zombie apocalypse can help individuals get ready for any major disaster. The zombie is not only a creature of horror; it serves as an effective, widely recognized tool for public health education.

Zombies in ancient history

The concept of the reanimated dead has been present in human history for thousands of years, appearing across various cultures and long beforethe modern germ theory or epidemiology did not exist. These beings were frequently a means for communities to comprehend anddescribe the natural environment and how illnesses spreadwithout scientific understanding.

The oldest written referenceto beings resembling modern zombies is mentioned in "The Epic of Gilgamesh"which was carved into stone tablets between 2000 and 1100 B.C.E. Furious when Gilgamesh refuses her marriage offer, the goddess Ishtar warns him, "I will unleash the dead to devour the living, I will make the dead outnumber the living." This old fear - the dead overpowering the living - closely resembles the idea of a rapidly spreading disease that quickly swamps the healthy.Hollywood has quickly embraced this idea in many zombie movies.

The origins of the flesh-eating corpse on screendate back to George Romero's 1968 classic "The Night of the Living Dead." You won't hear the word "zombie" in Romero's film, however – in the script,he called the creaturesmeat eaters." Similarly, in Danny Boyle's 2002 film28 Days Later," the terrifying creatures were referred to as the "infected." Both these terms, "flesh eaters" and "infected,"directly reflect public health issues- more precisely, the transmission of illness through bacteria or viruses and the necessity of quarantine to prevent the spread of those who are infected.

The origins of the word zombie are linked to the Haitian version. believed to date back to West Africa and words like ""nzambi," which translates to "creator" in the African Kongo language., or “"ndzumbi," which translates to "corpse" in the Mitsogo languagefrom Gabon. However, it was in Haitian Vodou,a faith rooted in Western African spiritual practicesamong individuals who were enslaved on Haiti's plantations, the idea took holdmost terrifying form.

According to Vodou, if someone dies prematurely or under unusual circumstances, priests have the ability to seize and control their spirit. Slave owners took advantage of this belief toprevent self-harm among enslaved individuals. To transform into a zombie –not alive yet still bound in servitude– was the ultimate horror. This cultural idea goes beyond illness to address societal trauma and the public health issue of forced labor.

Creatures resembling zombies across the globe

Across the globe, other Reanimated dead bodies appear in regional legends, frequently highlighting anxieties about incorrect burial, violent demise, or immoral behavior. Numerous stories regarding these unsettling beings not only explain how to avoid turning into one, but also outline methods to stop or hinder their spread. This emphasis on prevention and management lies at the core of public health.

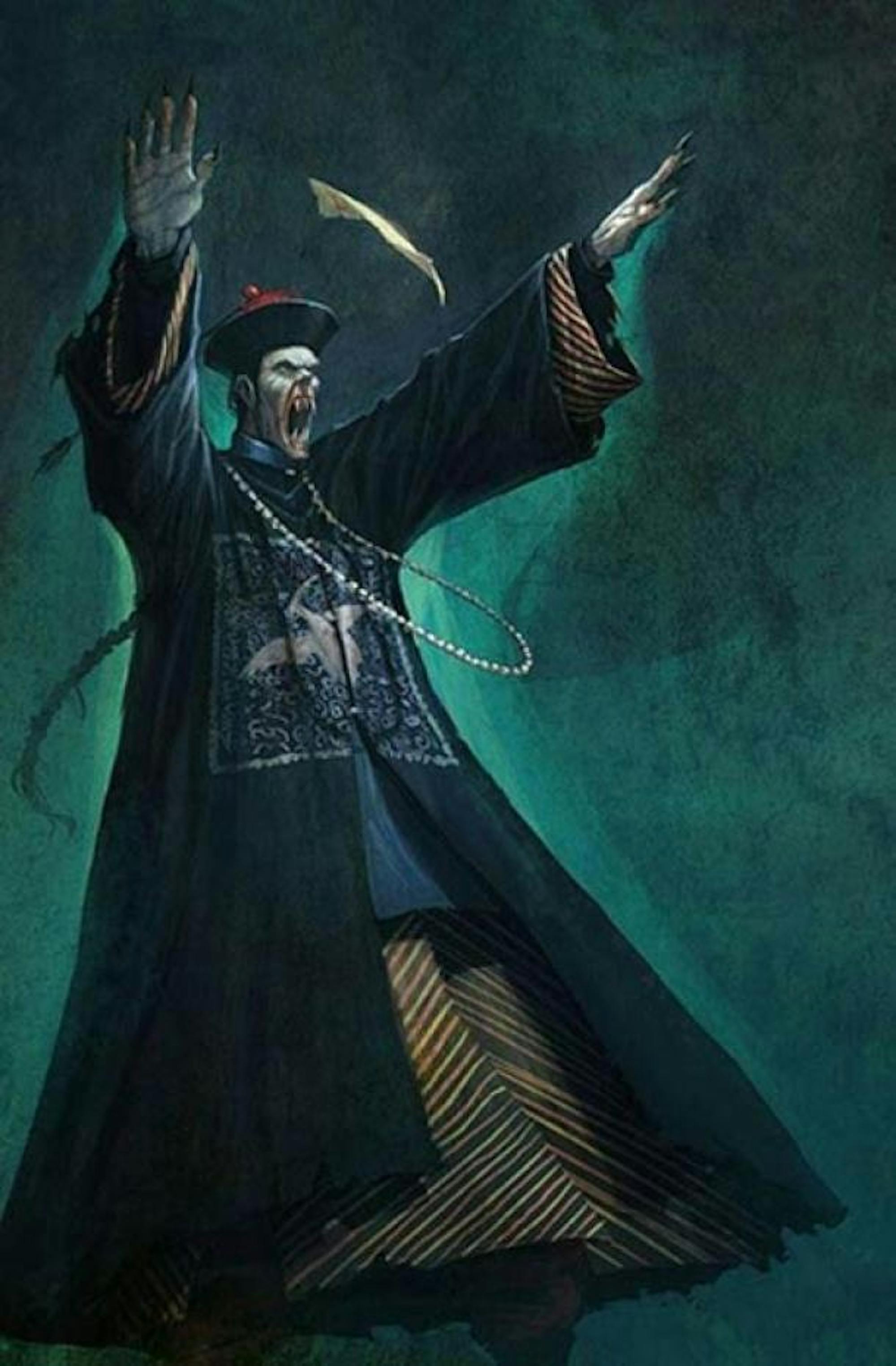

During the expansion of China’s Qing dynasty, which occurred between 1644 and 1911, a being called the jiangshi, or "hopping zombie," appeared duringwidespread dissatisfaction and inclusion of non-Chinese ethnic groups. The jiangshi were corpses experiencing rigor mortis and decayReborn when a soul was unable to depart after a sudden death. Rather than limping, these mythical beings would jump, and their way of attacking involved stealing a person's life energy, or qi.

Anxiety about a solitary, unsettled existence after death prompted families who had lost a relative far from hometo employ a Taoist monk to recover the bodyfor a proper burial among ancestors

In Scandinavia, the draugr – meaning "repeater" or "ghost" –was a being driven by vengeance. According to legend, draugrs usually came from people with malicious intentions or bodies that were not properly buried. Similar to zombies, they could infect others and turn them into draugrs. They would attack their victims by eating flesh, drinking blood, or causing them to go mad. The contagious aspect of draugrs serves as an example of how diseases spread. Additionally, their pattern of activity—often appearing at night during the winter months—is comparable toseasonal patterns of infectious disease spread.

During the medieval period, it was believed that beings known as revenants—dead bodies that emerged from their graves—roamed northern and western Europe. As recorded by 12th-century English historian William of Newburgh, these entitiesarose from the remaining life energyof individuals who had performed wicked actions throughout their lives or who met an abrupt end. Clericspeople's fears of turning into a revenant were fueledby asserting that these beings were fashioned by Satan. The suggested but horrifying preventive measure against this destiny was tocapture and dismantle these beingsand to incinerate the body parts, particularly the head.

Evidence from a medieval village in England indicates that communities followed this guidance. Archaeologists uncovered the village's burial site, and among the human remains dating from the 11th to 13th centuries, they discoveredfractured and scorched bones with cut marksThey demonstrate how a community might have implemented drastic actions to manage a feared spread or danger to public safety, resembling contemporary quarantine or elimination procedures.

One of the most notable commonality between these historical creatures and Hollywood zombies is that a significant number of them originate from an infectious substance. Once an outbreak happens, it becomes challenging to restore control, highlighting the importance of a swift public health reaction.

This piece is reprinted fromThe Conversation, a non-profit, independent news organization providing you with facts and reliable analysis to help you understand our complicated world. It was written by:Tom Duszynski, Indiana UniversityRead more:

- Some individuals enjoy frightening themselves in a world that's already full of fear — here's the psychology behind it

- Pancakes won't transform you into a zombie like in HBO's 'The Last of Us,' but mold found in flour has been causing illness in people for many years.

Tom Duszynski is not employed by, advises, owns stock in, or receives financial support from any company or organization that would gain from this article, and has not revealed any additional relevant affiliations outside of their academic position.